Imagining Better Care Systems — how to design accessible and inclusive workshops

Imagining Better Care Systems — how to design accessible and inclusive workshops

Part 1 of 2: our learnings from running three workshops to imagine better care futures

As we’ve discussed in previous posts care needs, as well as care costs, continue to grow faster than the supporting infrastructure and workforce.

The sector needs a radical change in order to meet care needs.

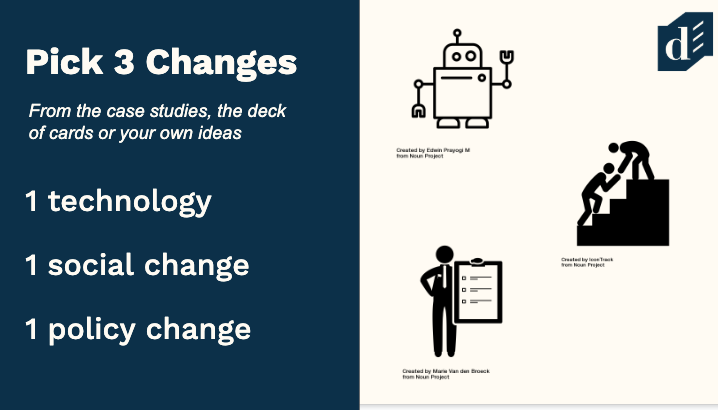

New technologies (such as robots that help us around the home) and policies (such as changing the legal definition of ‘care needs’) are undoubtedly going to have an effect.

But what impact will cutting edge technology and radical policy ideas have on the different people who are giving and receiving care?

For our research to be worthwhile, we need to learn from a range of people who interact with the care sector, not just the people with the most confidence and access to resources. We held three workshops with people who have personal and varied experiences of receiving, providing or exchanging care to learn more.

But people do not owe you their time and energy to attend or advise on events like these.

For many people energy, time and money are in short supply and their participation won’t be subsidised by their job.

We needed to do a good job for them, in order to do a good job ourselves.

At Doteveryone we’re committed to doing what we can to make our events as accessible and inclusive as possible. Therefore, a few things we believe you should aim to do when running events like these are to:

- Pay people for their time and cover their costs

- Design for the furthest first

- Offer support with coordinating logistics

- Be prepared to listen to anxieties, talk people through solutions, and accept ‘no’

- Put in the time and effort to earn trust.

But we don’t have all the answers. We can always learn and we can always do better. There were some things that we did not anticipate and things we could improve for next time. We thought it would be useful and interesting to share them, as well as some of the care futures we imagined in the workshops (see part 2).

Our approach and lessons learned

Pay people for their time and cover their costs

Accessibility isn’t just about physically getting to a space.

Barriers to attending events may be physical, organisational or even psychological: many vulnerable participants will have had negative experiences sharing their stories with institutions and officials.

Let’s start with finance.

Financial constraints affect many in the current care system. Half of care professionals are paid £7.50 or less an hour, with around 10% missing out on minimum wage. Carer’s allowance, for those who look after family members full time, is £64.50 a week. Around 30% of disabled people live in poverty.

Alongside the cost of travel to the venue and general subsistence costs, many would have to arrange cover and support for those they care for. As such, we decided to pay anyone who self-identified as a care professional, a carer, or a user of care services a £100 fee for the day. We also paid for everyone’s travel, and offered to purchase tickets and accommodation ourselves if required, and generally assisted with logistics surrounding the day.

What could we do better next time?

While for the most part, this worked well, a lesson for next time is to be clearer about when payments will be processed to manage expectations.

As employees, employers and freelancers we are used to receiving payment on monthly cycles. We didn’t anticipate needing to flag to attendees to expect payment within 30 days of the workshop. Some attendees were more used to being paid weekly so we received phone calls when the money hadn’t arrived within a week, as they had factored this additional income into their budgets.

While we did pay everyone promptly, according to our own expectations, next time we can be clearer and avoid these concerns.

Design for the furthest first

Quite a few of the people attending our workshops had specific cognitive access needs — we’d invited self-advocates with learning disabilities, dementia and brain injuries, and health conditions that can impact executive function.

But designing workshop materials for the “furthest first”, in this case those with cognitive accessibility as a top priority, had benefits for everyone. Many of our participants who didn’t have specific cognitive access needs had never taken part in a workshop like this before, some weren’t fluent in English, and attendees had very different levels of formal education.

Some attendees with physical disabilities, chronic health conditions, or who had been up in the night for caring responsibilities would experience fatigue. And others would have a variety of things competing for their attention — care home managers needing to take work calls, carers needing to check in on how family members were coping without them, and one disability rights lawyer fielding time-sensitive calls regarding a case.

Before designing the workshop contents, we asked attendees and carers their needs and preferences to ensure the language and structure would be accessible and clear to everyone.

They gave us specific instructions on things like font size, as well as more general suggestions on being accessible and inclusive without being patronising or limiting.

Solutions weren’t complicated.

We used size 24 font on written instructions, and icons to illustrate.

Our case studies included pictures, headlines, short summaries and ‘extra details’ segments so that people could choose the level of detail they wanted to engage with and to allow participation in a debate whether they’d read through every example on the page or not.

We decided early on to avoid jargon and technical language, have clear instructions and each exercise lead logically to the next. This helped us get better insights from our attendees. It gave people options about how much to read and how to engage and meant that the outputs didn’t become dominated by the most confident, educated or experienced people in the room.

What could we do better next time?

While this was a decent start, we would hope in future to have the time to check our materials with a proper easy read consultant service rather than rely on informal advice.

We’d also do better at signalling what parts of reading were optional and include some partially completed examples and personas to better invite people with less experience and confidence to edit and build on the materials.

Consider how people will experience as well as access the space

Physical accessibility was one of the simplest things to consider, because public venues need to adhere to legal accessibility requirements.

All of our workshop venues had step free-access and accessible toilets, although we did talk with security staff to allow us access to the closest accessible toilet and avoid attendees having to take a meandering journey to the public one.

What could we do better next time?

One thing we should have anticipated is that wheelchairs can block other wheelchairs. While we attempted to lay out a clear path around the room so people could see and discuss the various case studies, we still had a multi-wheelchair traffic jam on the day. This was easily fixed but next time we’d make sure we confirm the room layout with the venue on the phone (the room description didn’t specify pillars) and enforce a one-way system.

Be prepared to listen to anxieties and put in the time and effort to earn trust.

Lastly, a significant number of our participants faced risk and anxiety in taking part.

For people reliant on benefits and government-funded care and support services, there were concerns that attending an event that might look like “work” could be used as evidence that their services could be cut. Logically and legally this should not have been a concern, but the system is not always logical, and not everyone has access to legal support.

Frontline care staff had real concerns about being fired and blacklisted for being suspected of complaining or whistleblowing. In fact, so many participants in our first workshop asked not to be in photos that we decided not to publicise any photos from that day.

Telling one’s story in a semi-public setting can be an emotionally charged experience for people who must continually tell their life stories in order access benefits and services, and for people who feel they have been betrayed before. Several people told stories of opening up to social workers and assessors who had seemed genuinely friendly and supportive, but then having those conversations used as evidence for their services and payments to be cut.

Others talked about spending time, energy and money advising different services about access in similar workshop environments, only to feel that their views and efforts were overlooked; that their participation was just a tick box exercise.

We tried to be aware of this emotional context, build trust, to not take any defensiveness personally, not to push when people resisted interviews on emotional topics, and to be clear about the project’s timeline and plans. Paying people for their time also alleviated some anxiety; even if the day had no results, at least they weren’t out of pocket for taking part!

Only time will tell if we can be part of the change our participants hope for, but we take this responsibility seriously.

Know when to say ‘no’

Sometimes, we learned, the correct choice is not to engage. We had hoped to connect with a group of people who the Brandon Trust support whose complex needs make travel and phone interviews impossible. Some people they support had consented to participating in research by post. We hoped to turn questions and exercises from the workshop into a survey with easy read writing and illustrations.

As we were developing the project, staff from Brandon Trust with extensive experience in the field advised us that, on reflection, they worried we could harm vulnerable people simply through asking these questions. Participants who got the survey might worry that their support services would be changed or cut. So we decided not to go ahead with the survey in this form at this time and will explore ways to connect with this population in a safer way.

Caring about our participants’ wellbeing is the responsible, ethical thing to do. But it is also important from a methodological viewpoint. Participants who fear for their safety, their jobs or for the services they rely on may distort their answers to protect themselves and tell researchers want they think they want to hear.

We needed to be willing to hear difficult stories, to genuinely earn trust, to accept being told no.

Topping and tailing the day — allow ample time for introductions and close with a call to action

We wanted everyone taking part in the workshops to feel comfortable on the day and confident in knowing what was expected from them at every stage of the process. We also wanted to make sure we made the most of our time with them and that we had some fun in the process!

At the beginning of the day, we made sure to allow a lot of time for introductions. We wanted people to have time to share their stories at the pace and detail they wanted. Not only was this was critical research material for us, but it also and helped attendees build confidence and relationships to set them up for the rest of the day.

“Thank you so much for inviting me to participate. It really inspired me to feel more excited by health and care and to encourage change which had been a struggle for a while.”

Dementia Nurse

Sometimes running creative workshops like this, in a sector that has urgent needs can feel like a luxury or even a waste of the limited energy and resources available. So in the final exercise, inspired by a Social Movements workshop run by Jacqueline del Castillo at Manchester’s Social Care Futures, we took a step back and allowed 10 minutes for people to come up with one action we could take or one campaign we could start right now that could steer our present towards these better care futures.

This helped underscore the connection between imagination and action.

We came up with social media campaigns to share stories of care, petitions, and ways different organisations represented by our participants could connect.

It gave our participants a final jolt of inspiration, encouraged them to share contact details and make real, concrete plans to work together, buoyed up by the imaginativeness of the day.

We are enormously grateful to everyone who participated in the workshops, and everyone who couldn’t travel but let us visit their support groups or had an interview over the phone.

We got an incredible picture of the complicated web of needs and relationships in care and the ideas we explored will feed into the rest of our work going forward — we are currently in the process of turning some of the futures we imagined futures into a short film with Superflux.

What is clear is that, if we are able to include everyone and draw upon the enormous amount of experience, ideas, and creativity they have, then there is a lot of hope for a more sustainable, effective and fairer care system in future of robots, exoskeletons, and smart homes.

We’ve summarised some of the current issues and ideas for how tech could help us build a better care system that works for people in Part 2: five ideas for a fairer future.

More about the Better Care Systems Project

At Doteveryone, we believe that technology cannot replace care, but used well it could support radical social and structural change, taking us towards a future care system that is sustainable, fair and effective.

Our Better Care Systems project, supported by Google,org, aims to understand the current challenges facing the people who use care services, carers, care professionals, technologists, activists, providers and policymakers (including many people who fall under more than one of these labels), and explore how we can build better and fairer care systems in a future of robots, exoskeletons, and smart homes.

Want to get involved?

Contact us via [email protected].

And to stay informed on the general progress of this work, make sure you sign up for updates. (We won’t use this more than once a month).

Imagining Better Care Systems — how to design accessible and inclusive workshops was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.