We need a new conversation around care and automation

Doteveryone is currently running a project to explore how we can build better and fairer care systems in a future of robots, exoskeletons and smart homes.

Throughout the Better Care Systems project, we’re talking to carers, care professionals, technologists, activists, and people who use care services, (and many who fall under more than one of these too-limiting labels) about the current challenges and asking them to imagine possible new alternative futures of care in which the system is fairer, more sustainable and more effective.

This post explores how we commonly talk about AI, automation and care in the UK, how this is flawed, and imagines ways society and the care community can shape it for the better.

How we talk about care really matters.

The narratives around care shape our collective worldview, dictate the social status we confer on caregivers and how we view those in need of support. They define what constitutes caring and our expectations of who should provide it.

Care is on the cusp of unprecedented change wrought by technology and the potential for automation. Innovations from robotic exoskeletons to care worker platforms promise to improve every corner of the care ecosystem on a near-daily basis. This moment of flux represents an opportunity to start a long-overdue conversation about how we value care and the place it takes in our society, and to radically reshape our care system.

But the ways in which we currently talk about technology, automation and care in the UK mean we may fail to realise this important opportunity.

Recent research from the Reuters Institute finds media coverage of artificial intelligence as a whole to be highly-politicised (with right-leaning news outlets highlighting issues of economics and geopolitics, and left-leaning outlets focusing on ethical concerns around discrimination, algorithmic bias and privacy) and dominated by industry voices.¹ Tech-celebrities and “thought-leaders” across the political spectrum compete to win the minds of a public paralysed by conflicting messages and the sheer complexity and scale of the issues.

Meanwhile in discussions about care, people with lived experience of what’s it’s like to care and be cared for struggle to be heard. Unpaid carers, 40% of whom spend more than 20 hours a week caring² and 22% of whom live below the poverty line,² have little time for the luxury of participating in policy debates.

Changes in legislation intending to give care recipients a greater voice have proved problematic, with more than half of care providers reporting these advocacy arrangements are not working.⁴ In response, organisations like the Older People’s Advocacy Alliance have called for the establishment of a national independent advocacy body to support the voice of people in care.⁵ This demand that has so far gone unanswered.

Where technology and care overlap, these issues are exacerbated. We have a highly vocal tech sector, where 81% of the workers are men,⁶ creating technology for a largely silent care sector, where 84% of the work is done by women.⁷ This disconnect risks creating care technologies that don’t reflect the needs of care workers and their communities.

So here we uncover how the common narratives around AI, automation and care in the UK are flawed, and imagines ways society and the care community can shape it for the better.

The voices of automation

The RSA, in their 2017 report, The Age of Automation, outline the “four voices of automation” whose worldviews sit along a spectrum of anxiety about the prospect of the fourth industrial revolution. “Alarmists” foresee an inevitable trajectory of job losses, economic turmoil and rising inequality. On the other side of the coin, “Dreamers” see mass automation as an opportunity to radically restructure the economy for the better. “Incrementalists” characterise automation as a gradual process around which society can adapt. And finally, “Sceptics” point to the global plateauing of productivity as evidence that the innovative potential of artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics are vastly over-hyped.⁸

Each of these divergent camps of opinion is founded on its own cultural tropes around automation and robotics. Malicious autonomous machines like Hal 9000 or iRobot, along with Stephen Hawking’s warning that artificial general intelligence (AGI) “could spell the end of the human race” ⁹ clearly plant the seeds for alarmist thoughts to grow in the minds of the public. Dreamers draw on a body of techno-utopian thought championed by much of Silicon Valley¹⁰ and “fully-automated luxury communists”¹¹ halcyon visions of a post-work society where the profits of automation are enjoyed equally by all.

In the middle-ground, views of sceptics and incrementalists are embodied by Steve Wozniak’s climb-down from his view back in 2015 that “AGI will enslave humans as pets”, to two years later, being “not convinced that we’re really going to get to the point where they really can make an artificial brain”.¹²

These competing narratives around automation are accompanied by a sense that the challenges arising from it are somebody else’s problem, to be dealt with tomorrow. 75% of respondents to the 2018 British Social Attitudes Survey feel that machines will do many of the jobs currently done by humans in the next 10 years,¹³ but various other research finds less than a third of people are worried about losing their own job to automation in the short to medium term.¹⁴¹⁵¹⁶

This confused environment has given rise to an influencing industry which tries to sway opinion — both within the tech sector and among the public at large. Competition between ‘AI thought leaders’ is now so fierce that thinkers 360 has developed an influencer score and leaderboard for the top 20 global AI thought leaders.¹⁸ The scores were, inevitably, algorithmically generated.

The result is a public who feels like the issues surrounding AI and automation are beyond their collective control. People tune out in response to the complexity, uncertainty and absurdity of a discourse that, in the words of Carnegie Mellon machine learning Professor Zachary Lipton, is “so completely unhinged it’s impossible to tell what’s important and what’s not.”¹⁹

How do we talk about care?

Over the course of our lifetime, our relationship with care is always one of interdependence. It is a series of social contracts between families, communities and the state. When we nurture our children we pay it forward for a time when we hope they will care for us. Care within our communities is founded on reciprocity and shared understanding. The emotional labour we carry out in our workplaces and homes on a daily basis is the glue of our society.

But recent work by the Frameworks Institute analysing over 350 articles on children’s care in Scotland from 2015 to 2017 found that the broader social costs and effects of the care system are largely absent from media discourse. Instead, the articles frame care as an issue of narrow concern for care-recipients and those in their immediate orbit. A mear 17% mentioned social causes of the care experience such as poverty and lack of community resources, whilst 60% advanced an individualised story narrative.²⁰

These narratives don’t reflect the reality for those working in care, frustrations which are reflected in the comments of National Association of Care & Support Workers CEO Karolina Gerlich: “The media has a tendency to talk about person-centred care, which is not the whole story. It doesn’t show what care is about — relationships between the person giving, organisation delivering, family and community. We need to talk more about relationship-centered care.”

The inherently collective nature of care is also under-recognised in research and policy. In a landscape review of care research in the UK, Alisoun Milne and Mary Larkin describe how the majority of research focuses on assessing the efficacy of care services and the demographics of who provides care. This work in turn “tends to dominate public perception about caring, influences the type and extent of policy and support for carers and attracts funding from policy and health-related sources”. Research into care’s impact on the experiential aspects of care and social context, on the other hand, is “strong in capturing carers’ experiences, [but] has limited policy and service-related purchase”.²²

So, according to Daniel Busso, co-author of the Frameworks Institute report, this means the public are “provided with a set of stories about how the care system and the government are dysfunctional, ineffective and siloed. These stories undermine efforts to promote public sector solutions to improving care.”

A myopic focus on the travails of the public care sector and the individual dimensions of care over the collective, in research, policy and the media, shapes society’s understanding of it. As a result, we develop a narrow understanding of care, obscuring our view of the vital social infrastructure upon which is it built.

How do we talk about the automation of care?

When seen through the lens of technology, this incomplete picture has profound consequences.

When developers of care technologies see care as individualised and atomistic, the products they develop will serve those individual needs at the expense of communities and wider society.

This disconnect between the needs of the care ecosystem and the technologies designed to support it is exacerbated by the differences in the lived experiences of the care and tech sectors. Research from the Office of National Statistics has found the average woman in the UK gives 10 more hours a week of unpaid care than the average man, at an estimated value of £0.77 trillion a year to the UK economy.²³ And it’s estimated that women make up 84% of the care workforce,²⁴ in stark contrast to only 19% of the UK’s tech sector.²⁵

Sophie Varlow, founder of The Commons Platform, highlights how the subtler aspects of care can get lost in translation as a result: “If tech is only ever built by certain groups of people who don’t have to do certain forms of emotional labour, they instinctively think they will be picked up somewhere by someone without realising that is a personal expectation they have.”

Coding is language. Data tells stories. Where technology looks to quantify care into data points, determined by people far away from the realities of care, we simplify these stories. This renders the messier, qualitative, intuitive aspects of care invisible. By standardising metrics in pursuit of scale, we risk losing the local context and cultural specificity that cannot be ignored.

“If we think about one-size-fits-all solutions for care, where the only exchange is dollars for time, we lose out on a lot of this ecosystem of care that is rich and contributes to society indirectly.” — Amelia Abreu, Writer, User Experience Designer and Researcher

This metrification of care in the platform economy also places competitive pressures on carers. An exploration of market platforms for domestic work in the US by Data and Society found the need to constantly maintain digital profiles reduced the relative importance of workers’ actual care-giving skills. Instead, gaming the platform’s rating systems and self-branding becomes a priority.²⁶

Automation makes us conceptualise care as a series of discrete and measurable interactions.It implies caring can be replicated, and carers are displaceable. The result, as articulated by Karolina Gerlich, is a community of “care workers who are terrified — they think they are going to be replaced. Some [technology developers] introduce products to care providers by saying this is going to save you three people”

With innovation directed away from the needs of communities and some care technologies, in fact, placing new stresses on care workers, the quality of care will suffer. Paradoxically, technology simultaneously threatens carers whilst presenting itself as the solution to falling standards and funding crises in the formal care sector.

This tension is reflected in the highly politicised and polarised media debates around AI, automated technologies and their applications to care.²⁷

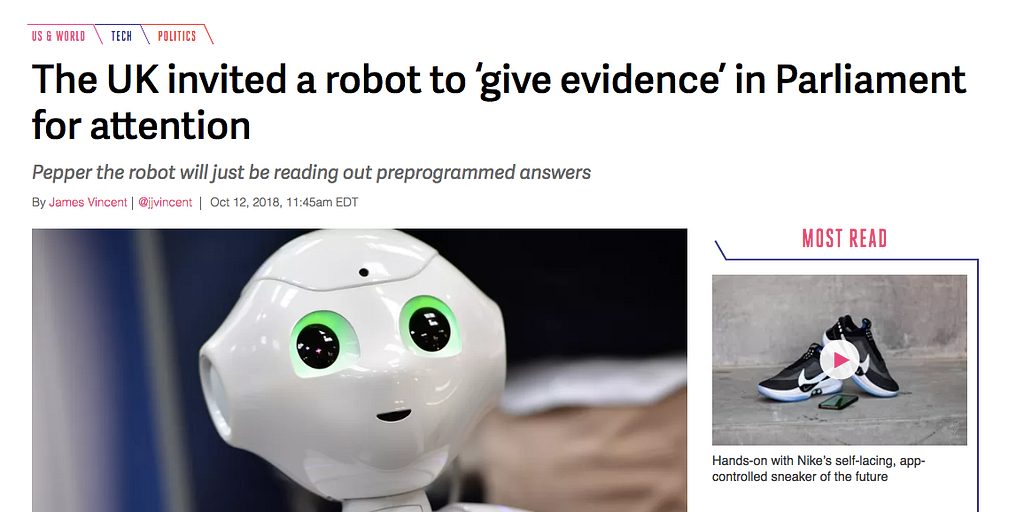

These debates are embodied by Pepper the robot’s appearance before the Education Select Committee in October 2018.²⁸ Some in the media welcomed the inclusion of Pepper and its pre-scripted responses, as part of a discussion around the role increased automation and robotics might play in the workplaces and classrooms of the future, portraying it as demonstration of where AI-enabled conversation robotics could take us. But others saw it as proof of a cynical PR-drive from the tech industry.

Conflicting reporting plays into our existing biases, reinforcing our worldviews and closing down the space for much-needed honest reflection on the progress and trajectory of such technologies. Dr Chris Papadopoulos, part of a team developing and evaluating culturally competent robots as part of the EU H2020-Japanese government-funded ‘CARESSES’ research project, sums up this challenge: “We have to be honest about where the technology is at, where it could go, rather than unnecessarily present scripted displays of interactions with Pepper that may reinforce or add to the stigma of social robotics and play into the agenda of discouraging robotics that some media have.”

How we need to talk about care and automation

How we talk about care — in the media, in policy, our workplaces, communities and families — matters.

But how we currently talk about care leaves us at risk of undermining the very foundations upon which this vital social infrastructure rests.

The disruptive potential of automation presents an unprecedented opportunity to reimagine care, bringing together the public, policy-makers, the tech sector, civil society and the care sector to articulate a common vision for the future.

To start this conversation we need to move away from speaking about care as an individual right and reframe it as a collective social contract. Many people interviewed for this essay echoed this view. Annemarie Naylor, Director of Policy and Strategy at Future Care Capital, for example spoke of the need for a rhetorical shift from “my health and care to our health and care”. Guided by a new Care Covenant, she argued that there’s the scope to approach wellbeing as a “common pool resource to be collectively stewarded”.

It’s also important to “show individuals in context”, as argued by Daniel Busso: “we need to inoculate against the idea that people’s life outcomes are solely the result of their willpower or whether they make good choices. Members of the public need to be reminded that, if someone is thriving, it’s because they are tapped into a network of community support and social resources.”

We must all help to surface these hidden societal contributions, tell more diverse care stories and reject unhelpful cliches around care.

Developing new terms and language can also help to make explicit the aspects of care that are currently underappreciated and invisible. In the debates around the future of work, policymakers should give less focus to ongoing re-training, “skills diversification” and even universal basic income. Skills mastery, focusing on opportunities for workers to raise standards in their current sectors and remain in jobs that are part of their identities deserves just as much attention.

Ensuring we see care in its broadest context and establishing this common language lays the foundations for society to have an honest and nuanced discussion about the future role of technology in care.

“We need to figure out which elements of care are enabling people to enjoy their work, relationships to flourish, and communities to develop and which elements are exploitative and exhausting. It’s these latter areas that we can consciously try to reduce or even eliminate, leaving only the tasks which let humans flourish.” — Helen Hester, University of West London

Care experiences aren’t homogenous. Research highlighting the differing experiences of socially assistive robots, where some caregivers feel the technology enables them to give better care and some recipients feel infantilised, reminds us of this.³¹

We must also create equal space for the views of other people within the care ecosystem to be heard, and where the circumstances of care mean dialogue in the moment is challenging (for example in care of people with advanced alzheimer’s disease), creative thinking is needed. The use of Advance Directives³² that allow people to specify whether they consent to the use of care technologies in their future care are one small-scale example if how this could be done.

Carers must be at the heart of all these conversations. Bringing technologists together with carers to co-create solutions will be vital in strengthening the care advocacy sector and strengthening support for time-poor unpaid carers.

If we fail to do this?

We’re at risk of going down a path where automation focuses on the high-value human side of caregiving and drudgery is left untouched.

By affirming the needs we as a nation would like care technologies to address, we give tech developers a mandate to innovate in society’s interest, and set boundaries around the parts of care too sacred for technologies to disrupt.

Want to get involved?

Contact us via [email protected].

And to stay informed on the general progress of this work, make sure you sign up for updates. (We won’t use this more than once a month).

If you enjoyed this, please click the 👏 button and share to help others find it! Feel free to leave a comment below.

References

- https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/risj-review/uk-media-coverage-artificial-intelligence-dominated-industry-and-industry-sources

- https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/POST-PN-0582

- https://doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Carers_and_poverty_in_the_UK_-_full_report.pdf

- https://doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/CA-advocacy-commissioning-research-report.pdf

- https://www.communitycare.co.uk/2015/08/03/care-act-right-advocacy-undermined-chaotic-commissioning-lack-resources/

- https://technation.io/insights/report-2018/

- https://www.hrzone.com/talent/acquisition/gender-imbalance-in-the-social-care-sector-time-to-plug-the-gap

- https://doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/rsa_the-age-of-automation-report.pdf

- https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/05/14/how-frightened-should-we-be-of-ai

- https://medium.com/@thomas_klaffke/technological-utopianism-in-silicon-valley-bd38a0e4c047

- https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/mar/18/fully-automated-luxury-communism-robots-employment

- https://www.wired.com/2017/04/steve-wozniak-silicon-valleys-nerdiest-legend/

- https://doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/bsa35_work.pdf

- ibid

- https://www.britishscienceassociation.org/news/rise-of-artificial-intelligence-is-a-threat-to-humanity

- https://www.demos.co.uk/project/public-views-on-technology-futures/

- https://www.c4isrnet.com/thought-leadership/2018/06/25/what-you-need-to-be-reading-and-watching-to-become-an-ai-thought-leader/

- https://www.thinkers360.com/top-20-global-thought-leaders-on-ai-october-2018/

- https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2018/jul/25/ai-artificial-intelligence-social-media-bots-wrong

- https://doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/robertson-mcffa-2018-final.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/jun/25/only-about-half-the-mums-who-come-through-my-door-leave-with-their-baby

- https://doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/knowledge20generation20hsc20version.pdf

- https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/oct/03/british-people-do-more-than-1-trillion-of-housework-each-year-unpaid

- https://www.hrzone.com/talent/acquisition/gender-imbalance-in-the-social-care-sector-time-to-plug-the-gap

- https://technation.io/insights/report-2018/

- https://datasociety.net/output/beyond-disruption/

- https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/risj-review/uk-media-coverage-artificial-intelligence-dominated-industry-and-industry-sources

- https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/education-committee/news-parliament-2017/fourth-industrial-revolution-pepper-robot-evidence-17-19/

- https://www.theverge.com/2018/10/12/17967752/uk-parliament-pepper-robot-invited-evidence-select-committee

- https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/pepper-robot-mp-questions-parliament-answers-education-select-committee-a8586511.html

- https://doteveryone.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Robotics-and-AI-in-social-care-Final-report.pdf

- https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/advance-care-planning-healthcare-directives

We need a new conversation around care and automation was originally published in Doteveryone on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.